Up

Fabric Data

Contact us:

Simply Circus, Inc

info@simplycircus.com

86 Los Angeles St

Newton, MA 02458

617-527-0667

617-431-7352 (Gym)

| |

AERIAL RIGGING WEEK - Aug 29 - Sep 2, 2011

Want to learn more about rigging? Simply Circus is hosting a week

long Aerial Rigging workshop! For more information, or to sign up, click here!

Table of Contents

- 1.

About this FAQ

- 1.1. Copyright

- 1.2. Latest version

- 1.3. Questions about the Simply Circus Wiki

- 1.4. Disclaimer

- 2. General

Questions About Aerial Arts

- 3. Names

and Descriptions of individual Aerial Apparatus

- 3.1. Aerial Hoop

- 3.2. Aerial Silks

- 3.3. Cloud Swing

- 3.4. Corde Lisse

- 3.5. Cradle

- 3.6. Hair Hang

- 3.7. Russian Swing

- 3.8. Shoot-Through Ladder

- 3.9. Spanish Web

- 3.10 Straps

- 3.11. Trapeze

- 3.11.1. Static Trapeze

- 3.11.2. Swinging Trapeze

- 3.11.3. Flying Trapeze

- 3.11.4. Low Casting

- 3.11.5. Washington Trapeze

- 3.11.6. Dance Trapeze

- 3.11.7. Multiple Trapeze

- 3.11.8. French Trapeze

- 4.

Hand and Body Care for Aerialists

- 4.1. Basic Hand Care

- 4.2. Calluses

- 4.3. Caring for Rips

- 4.4. Caring for Swollen Knuckles

- 4.5. Toughening up the Skin

- 4.6. Aches, Pains and Other Soreness

- 5.

Better Hand Grips

- 5.1. Wrapping Metal apparatus

- 5.2. Chalk, Rosin and other such products

- 5.3. Hand Grip Aids

- 6.

Selecting Aerial Apparatus

- 6.1. Selecting an Aerial Hoop

- 6.2. Selecting a Trapeze Bar

- 6.2.1. Notes on wooden trapeze bars

- 6.3. Selecting Aerial Silks

- 6.4. Selecting a Web (Spanish Web, Corde Lisse, Cloud Swing,

etc)

- 7.

Inspecting and Maintaining Aerial Apparatus

- 7.1. Metal Apparatus (Lyra, Trapeze Bars, etc)

- 7.1.1. Cursory inspection

- 7.1.2. Full Inspection

- 7.2. Rope based Apparatus (Spanish Web, Corde Lisse, Cloud Swing, etc)

- 7.2.1. Cursory inspection

- 7.3. Aerial Fabrics

- 7.3.1. Cursory inspection

- 7.3.2. Full inspection

- 8.

Rigging

- 8.1. General Rigging Questions and Theory

- 8.2. More on Weights and Measures

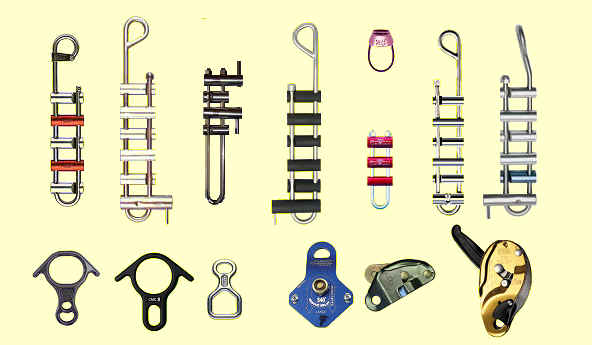

- 8.3. Rigging Components

- 8.3.1. Choice in Materials

- 8.3.2. Choice of Components

- 8.3.3. Knots, hitches and splices

- 8.4. Questions About Aerial Rigs and Mount Points

- 8.5. Questions About Rigging Specific Apparatus

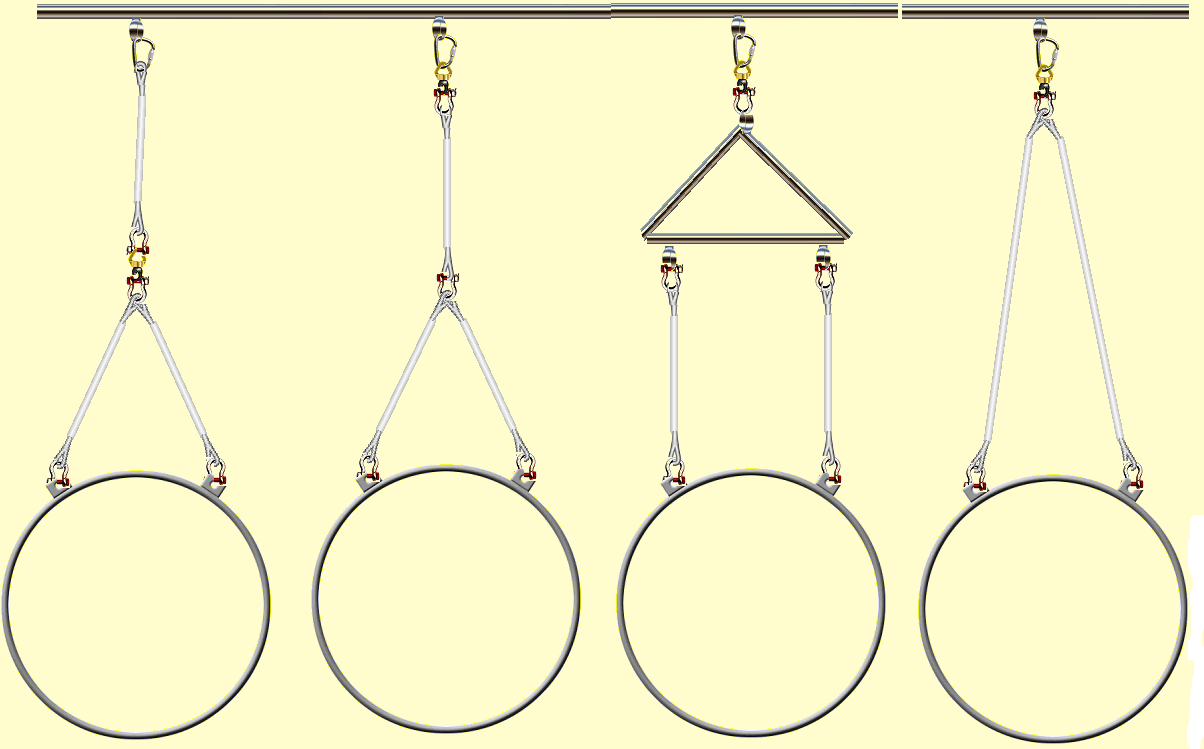

- 8.5.1. Aerial Hoop / Lyra

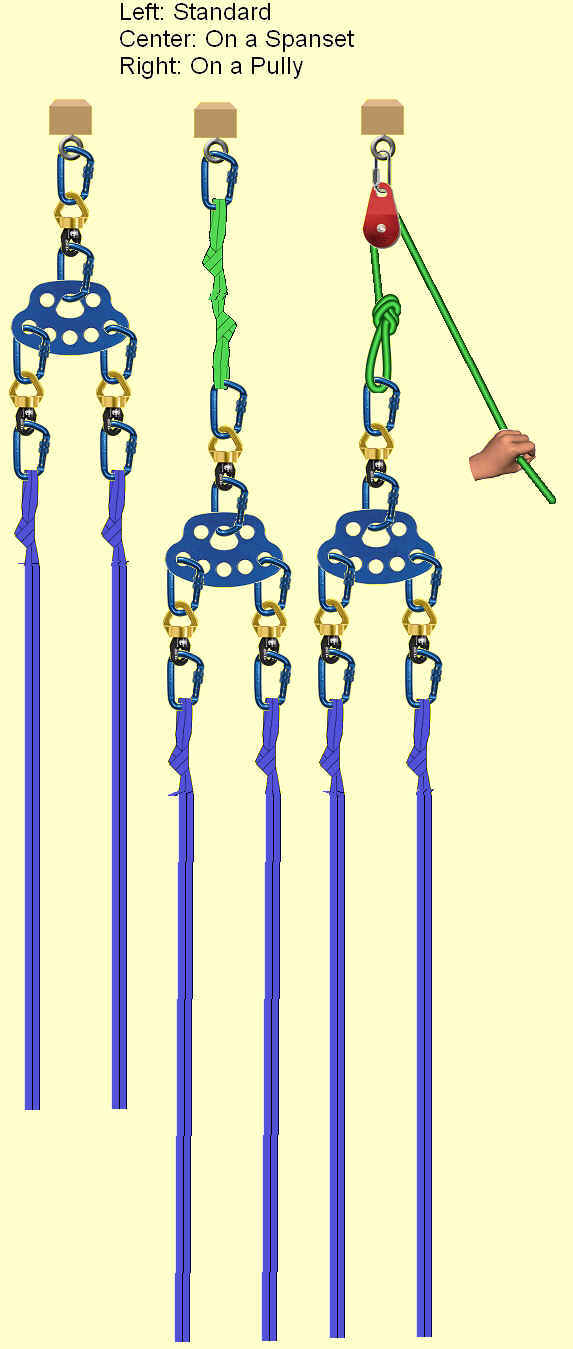

- 8.5.1.1. Rigging Diagram - Single Tab

- 8.5.1.2. Rigging Diagram - Double Tab

- 8.5.2. Aerial Fabrics

- 8.5.3. Cloud Swing

- 8.5.3.1. Rigging Diagram - Single Mount Point

- 8.5.3.2. Rigging Diagram - Double Mount Points

- 8.5.4. Corde Lisse / Spanish Web

- 8.5.4.1. Rigging Diagram

- 8.5.4.2 Attaching Hand Loops

- 8.5.5. Hair Hang

- 8.5.5.1. Hair Hang on a Pulley Diagram

- 8.5.6. Trapeze

- 8.5.6.1. Static or Swinging Trapeze Diagram

- 8.5.6.2. Dance Trapeze Diagram

- 8.5.6.3. Dance Trapeze on a Pulley Diagram

- 8.5.7 Straps

- 9.

Liability and Insurance

- 10.

Aerial Arts and Rigging Resources

- 10.1. Mailing Lists

- 10.2. Websites

- 10.3. Books on Aerial Arts and Rigging

- 10.4. Videos on Aerial Arts and Rigging

- 5.4.1. Finding videos on the internet

- 10.5. Software

- 10.6. Equipment Vendors

1. About this FAQ

1.1 Copyright

This document is copyright 2006 by Steven Santos / Simply Circus, Inc. (www.SimplyCircus.com),

all rights reserved. This document can not be reproduced without the expressed

written consent of Steven Santos / Simply Circus, Inc. This includes

posting this FAQ to any other website without permission. If you run an

aerial arts program and want to post a copy of this FAQ on your website, print

it up and distribute it to your students, or make other such use of it, you need

to ask.

1.2 Latest version

The latest version of this document can always be found at:

http://community.simplycircus.com/tutorials/aerial_arts_faq.htm

1.3 Questions about the Simply Circus Wiki

Q. What is the Simply Circus Wiki?

A. The Simply Circus Wiki is one of the primary educational and knowledge

management tools used by Simply Circus to develop, store and share our written

knowledge of circus arts. The wiki was created by, and is edited and maintained

by Simply Circus.

Q. Who is this wiki designed for?

A. This wiki is a resource intended for the students of Simply Circus.

Q. Why isn't the entire wiki open to the public?

A. We have made a select number of the resources on this wiki available to

the public. While we understand that access to the entire wiki would be

extremely useful to many others, its not fair for our students to pay for this

resource (via class fees or electronic access fees), and everyone else get it

for free. We will continue to make selected articles available to the public on

a case-by-case basis.

Q. If you open the wiki up, wouldn't the influx of people help to maintain

it, making it less expensive to maintain, and their forth viable to give to

everyone?

A. We have experimented with this a few times, all unsuccessfully.

We tried seeding Wikipedia with circus skills articles. We did a major

rewrite of the Circus

Skills page back in July

of 2005 to bring that page in line with the equivalent page on the Simply

Circus wiki, and we have made many edits to it since then to keep it more or

less inline with our page. We created and seeded a number of other Wikipedia

circus articles with information copied directly (though not in the entirety)

from entries from our wiki (edits by cirque115, 71.243.107.218 and 68.160.12.57

are the same people maintaining this wiki). After 9 months, the result has been

very little outside contribution, with many article having never had another

contributor edit them.

We had marginally more success contributing to the aerial riggers wiki. We

contributed an article on rigging Chinese poles. This article drew a number of

very useful comments, however at this time, the Chinese poles article is the

only full article on the Arial riggers wiki. (UPDATE: The Aerial Riggers WIKI is

no more).

While we have not yet been successful, we might be willing to try again. If

you think you have an idea of how to make it work, let us know, we are more than

happy to entertain the idea.

Q. OK, the wiki is not freely available to the public. Can I buy access to

it?

A. We are exploring the various isues involved in how that would work. We

may have something in the Winter of 2010.

Q. Who can I contact with other questions about this wiki / FAQ, or

suggested additions to this FAQ?

A. You can send all such comments to: Info@SimplyCircus.com

1.4 Disclaimer

Suspending people in mid-air is inherently dangerous. Damage to persons and

property, including death, can result. This FAQ is an attempt to share knowledge

and experience and to promote safety. But do not rely on anything you read here

without verifying its accuracy and applicability to what you are doing.

Neither the authors of this FAQ nor Simply Circus Inc. makes any

representations as to the safety or appropriateness of any practice or equipment

recommendation contained herein. Always consult with your own qualified expert.

** If you do follow any practices presented here, **

** know that you do so at your own risk.

**

It is very important that each of us understands the limitations of our own

knowledge, experience and ability. We need to know what we don�t know, and

know what we can and can�t do safely. If you have any doubt at all, get

professional expert help.

We also make no representation about the legality of any particular practice.

All jurisdictions have codes and regulations which may apply to what you are

doing. Be sure to ensure your compliance with all such applicable codes and

regulations, as well as any limitations which may be required by insurance

companies.

2. General Questions About Aerial Arts

Q. Are Aerial Arts Safe?

A. At the recreational level, so long as it is done with proper equipment,

training and supervision, aerial arts are as safe as any other recreational

sport or rigorous physical activity you may engage in.

Q. What aerial arts exist?

A. There are many aerial arts in common use. See the next section of this

FAQ for a list and description of the various aerial apparatus.

Q. Where can I find a book, video or tutorial on performing aerial skills?

A. You can check the resources section of this FAQ for helpful tutorials,

websites, books and videos on aerial arts. We strongly suggest you talk with

your aerial instructor about what you read/watch.

Q. I have seen people do this aerial arts stuff, and it doesn't look that

hard. Do I really need an instructor, and if so for what?

A. A good instructor/coach is highly recommended. A qualified instructor

will help you to learn the basic skills of the apparatus you are training on. A

good coach will help you map out a training route, give you ideas for training,

help you problem solve, keep you excited about the art, and most importantly

help you learn how to do a lot of this on your own.

Q. How do I rig XXX?

A. If you have to ask, you probably shouldn't be rigging it. In this FAQ we

do include enough basic rigging information that you should be able to get a

general idea of some basic rigging concepts, and understand generally how an

apparatus should be rigged. We include this for informational purposes only.

Consult your own qualified rigger to rig anything that a person will actually

fly on.

3. Names and Descriptions of individual Aerial Apparatus

In this section we try to give you the names and brief descriptions of the

various aerial apparatus in general use. Please note that when more than one

name exists for a given art, we have used the most common name, and given the

alternative names in the text.

3.1 Aerial Hoop

Aerial

Hoop, also known as "Circeaux" and "Lyra", is a steel

apparatus that looks like a suspended hula-hoop. Aerial hoops are usually

available in single tab and double tab configurations. The act itself usually

combines static and swinging trapeze skills with held poses and postures.

3.2 Aerial Silks

Silks,

also known as "Tissues" or "Fabrics", is an apparatus

consisting of a long piece of cloth with the center of the cloth suspended from

above. The act itself involves one or more flyers performing held postures,

wraps and drops. (Click Here to Order Aerial Fabrics)

3.3 Cloud Swing

Cloud

Swing is an aerial apparatus that resembles a Spanish web in the type,

length and width of material, but has loops on each end of the apparatus that

are fastened to mount points, with the swing itself hanging in a V-shape. Hand

and foot loops are typically attached loops to secure hand and foot dives. The

act itself usually combines static and swinging trapeze skills, drops, dives,

holds and rebound lifts. "Mexican Cloud Swing" is a variation on the

cloud swing, but without the hand and foot loops. Instead, the performer uses

their bodies to tie knots in the swing.

3.4 Corde Lisse

Corde

Lisse, also known as "Rope" or "Smooth Rope", is an

aerial apparatus that resembles a vertically hanging rope, but it is usually

made from soft cotton about 25-30mm thick, with a loop on the top side of the

rope. The act itself usually combines held postures, wraps and drops.

3.5 Cradle

Cradle,

also known as "Casting Cradle" is a an aerial apparatus resembling a

large rectangular frame. The frame can be fixed (static or freestanding) or

swinging. The act itself involves two performers, the first being the catcher,

and the second being the flyer. The catcher hangs by his or her knees from the

frame, while the flyer swings holding on to the catchers hands. The flyer

performs releases at the top of the swing and is re-caught in mid air. The flyer

usually starts and end standing on the frame above the catcher.

3.6 Hair Hang

Hair

Hang is a method of rigging a performers hair to allow aerial flight. The

act itself involves a performer performing various poses, spinning, and doing

other tricks while suspended.

3.7 Russian Swing

Russian

Swing is an aerial apparatus most closely resembling a large playground

swing. The seat is replaced by a platform (usually about 4'x6') and the chains

of the playground swing are replaced by four solid arms. The swing hangs from a

frame very much resembling a traditional double A-frame swing set frame. The

Russian Swing has the ability to catapult a performer over 30 feet in the air.

The act itself is most closely related to the teeterboard (aka Korean Plank),

with the flyers performing somersaults, twists and other aerial acrobatics

before landing on crash mats, nets or other such landing areas.

3.8 Shoot-Through Ladder

Shoot-Through

Ladder is a custom built aerial apparatus resembling a metal ladder

revolving around a central axle. On one half of the ladder the rungs have been

replaced with a trapeze. The act itself involves one flyer balancing the ladder,

while a second performer does static or swinging trapeze skills on the attached

trapeze bar. The name "Shoot-Through Ladder" comes from the ability of

the trapeze flyer to swing or shoot through the ladder.

3.9 Spanish Web

Spanish

Web is an aerial apparatus almost identical to the Corde Lisse, but with the

addition of loops for hands or feet. The act itself involves everything that can

be done with Corde Lisse, as well as many spinning motions made possible with

the additional hand loops. A "web sitter" is often used to pull

tension on the bottom of the web and to turn the web, spinning the flyer.

3.10 Straps

Straps,

also known as "Aerial Straps" and "Aerial Ribbon", is a

cotton or nylon web apparatus that looks like two suspended ribbons. Straps are

available in various configurations, including those with various types of loops

at the ends and those without loops. The act itself usually includes held poses

and postures done on the straps, dance moves performed on the floor away from

the straps, partner acrobatics done on and off the straps as well as having the

straps pulled up and let down during the act.

3.11 Trapeze

Trapeze

is the overall name for a collection of closely related aerial apparatus. All

trapezes are basically one or more suspended horizontal bars with vertical lines

attaching it to the overhead mount point or points.

3.11.1 Static Trapeze

Static

Trapeze is a trapeze that is not used for swinging. Static Trapeze is

usually 6 feet or more off the ground. The act itself most commonly involves

poses, hangs, drops and rope skills.

3.11.2 Swinging Trapeze

Swinging

Trapeze is a trapeze that is used for swinging. Swinging trapezes usually

have a 12 foot swing (the distance from the mount point to the trapeze bar),

with the bar at least 10 feet off the ground. The act itself usually involves

all of the skills used in static trapeze, as well as skills that revolve around

the swing of the trapeze.

3.11.3 Flying Trapeze

Flying

Trapeze is really two trapezes. The first is virtually identical to a

swinging trapeze, with the addition of a raised platform for the flyer to start

their swing from. The second catch trapeze is typically a smaller straight armed

swinging trapeze. The act itself usually involves all aspects of swinging

trapeze, as well as skills revolving around jumping from trapeze to trapeze, or

from trapeze to catcher.

3.11.4 Low Casting

Low

Casting is a mini flying trapeze rig. The act itself uses various flying and

partner trapeze skills.

3.11.5 Washington Trapeze

Washington

Trapeze, also known as "Heavy Trapeze", is a variation on static

and swinging trapeze. The trapeze bar used for Washington Trapeze is typically

much heavier than a normal trapeze bar, and has a small (~4" round)

headstand platform on it. Washington Trapeze typically involves all aspects of

static and swinging trapeze, with the addition of various headstand skills

performed on the bar.

Dance

Trapeze is a low trapeze mounted to a single point. Dance Trapeze combines

aspects of static trapeze, swinging trapeze, modern dance and many other

disciplines to form a fairly unique art form.

3.11.7 Multiple Trapeze

Multiple

Trapezes come in a number of shapes and sizes. The most common multiple

trapeze is the Double Trapeze (available in side-by-side and over-under

configurations). The Triple Trapeze (as well as larger multiples, available in

side-by-side, over-under and mixed configurations) are also commonly found. As

the name implies, these apparatuses are designed for use by multiple

simultaneous flyers, and allow for a variety of additional skills to be

performed on the apparatus. The last multiple is known as the Shaped Trapeze.

These are typically custom build apparatus designed for specific acts or shows,

and can take virtually any shape imaginable.

3.11.8 French Trapeze

French

Trapeze is a variation on Multiple trapeze where two performers perform

combinations of static trapeze skills as well various partner lifting skills

where one performer holds the other and manipulates them into a variety of

positions and poses.

4. Hand and Body Care for Aerialists

As an aerialist, you must take good care of your hands and body. The key

points to good hand care are basic hand care (regular cleaning and moisturizing

of the hands), care of calluses, and care of rips. We have also included some

notes on swollen knuckles and toughening up the skin. Recently, we have also

begun including some information on general body care for aerialists as well.

4.1 Basic Hand Care

Grip aids (such as Chalk or rosin) tend to dehydrate the skin. To help

counter this effect make sure you wash your hands and wrists thoroughly with hot

water and a good soap as soon as you complete your aerial workout. Use scrub

brushes (such as a surgeon's scrub brush) to help get every bit of the

"grip aid" off. While the skin is still soft and the pores still open,

you should use a good quality hand lotion (such as Vaseline intensive care or

Corn Huskers) to replenish the moisture in the skin.

4.2 Calluses

There is no way to prevent the formation of calluses on the hands of an

aerialist. Thankfully, having that tough skin on the hands is a good thing, as

long as you take care of it and remember that those calluses have to be flexible

and supple.

You should always keep your calluses trimmed. Take a look in the foot care

isle of your local pharmacy for a range of products designed to trim and care

for calluses. Among the more commonly used callus care tools are pumice stones

and callus razors.

Remember, dry, tough calluses will rip sooner than moist ones, so pay close

attention to your basic hand care!

For one method of removing calluses from the hands, see the calluses removal

tutorial at http://www.beastskills.com/calluses.htm

4.3 Caring for Rips

The most common cause of blisters and rips is over gripping of the apparatus.

If your hand is in the proper place (with the bar at the base of the fingers,

not centered in the palm) you will have less of the sliding and friction that

causes most blisters and tears.

The second most common cause of blisters and rips is gripping the apparatus

too tightly. remember that you don't have to choke the life out of the apparatus

to stay on.

When you do get a rip, make sure you clean your hands carefully. Use a

disinfectant, such as hydrogen peroxide or Betadine on the open wounds. You

might want to follow that up with a moisturizing agent, such as Neosporin or

other moisturizing antibiotic ointment. The key to healing a rip is to keep the

new skin supple as it toughens up during the healing process (again, basic hand

care).

Swollen knuckles are sometimes a problem when first learning vertical apparatus such as silks and Spanish web, as

holding these vertical apparatus strains your fingers more than say holding a

trapeze bar. As you build strength in your hands and fingers, this should go

away naturally. Ice and ibuprofen applied / taken after a workout is also known

to help. Make sure you discuss this issue with your aerial coach or instructor.

4.5 Toughening up the Skin

Aerialists need to develop tough skin. The following are common suggestions

for toughening up the skin:

- The sandpaper method. Rubbing your hands with sandpaper daily or every

other day basis works well.

- Tincture of Benzoin. Available from any running supply house, this is

known to toughen up skin, and it acts as an adhesive for keeping bandages on

- Cramer's "Tuff Skin" spray is also know to toughen up the skin

(and provide extra grip). It is available from various medical supply

companies.

- Urine. The acidity of the yellow stuff will help toughen up your hands.

- Diluted white vinegar. Same effect as the yellow stuff, but without the

associated germs, smells and general yuck factor.

4.6. Aches, Pains and Other Soreness

Q. Is it normal to have aches and pains from doing aerials?

A. Yes, it is. Aches, pains, soreness, and fatigue are all common

problems for aerialists. While these are common problems, their is a lot you can

do to help reduce these issues

Q. Why do I have these aches and pains?

A. Their are a number of factors that can cause an aerialist aches and

pains. For a new aerialist, soreness is usually caused by using muscles

you are not used to using. We recommend speaking with your aerial coach

about your specific issues.

Q. What should I do prior to, during and after an aerial session to help

reduce the aches and pains?

A. Their are a number of things that can help reduce the pains, including:

- Hydrate before, during and after any aerial session. Being

dehydrated can significantly increase muscle fatigue and soreness, as well

as increasing the time it takes to build up the muscles you are now using.

- Keep your muscles warm. Keeping your muscles warm improves blood

flow to those areas, which gives you greater flexibility.

- Do a cardio warm-up prior to doing any aerial arts

- Stretch out after you have warmed up

- Use warm-ups, sweat suits or other items of clothing to keep warm

- Keep moving, even while you are waiting

- Use Aspirin, ibuprofen or other over the counter pain medication after a

hard work out, or when expecting aches/pains to help reduce inflammation.

(Note: Check with your doctor, and always follow the label!

- Ice sore muscles

- Take warm bathes to warm up stiff muscles

- Use warming gels such as Tiger Balm on stiff muscles

5. Better Hand Grips

A good hand grip is extremely important when it comes to aerials. Different

5.1 Wrapping Metal apparatus

Metal aerial apparatus (trapeze bars, Lyra, etc) are generally wrapped with

tape to help with grip. In general, you want to use a one-inch wide,

non-zinc oxide athletic tape (Zinc Oxide is what makes taped bars feel extra

sticky, or like it is coated in residue). Hockey tape and bicycle

handlebar tape are also acceptable.

Start taping at one end of the bar, and continue all the way across to the

other side of the bar, overlapping the tape by about a half inch each wrap (for

a total of two layers of tape). Try to make your lines match up as closely

as possible without overlapping (no third layers!)

\ \ - First turn

\\ \ - Second turn

\\\ \ - Third turn

\\\\ \ - Forth turn (etc.)

When you finish, you should have a nice, smooth surface to grip your

apparatus. When you have finished wrapping your metal apparatus,

apply gymnastics chalk to taste.

When rewrapping, make sure to remove all tape and glue residue before

starting to rewrap the apparatus

5.2 Chalk, Rosin and other such products

A number of products are regularly suggested on the trapeze@yahoogroups.com

for getting a better grip on various aerial apparatus. The following

are the most common suggestions:

- Gymnastics Chalk. Available from various gymnastics supply houses,

chalk helps the flyer to grip metal apparatus, as well as preventing the

apparatus from becoming sticky or slippery.

- Spray chalk. Found under various brand names, spray chalk is a powdered

chalk mixed with medical grade alcohol. It spreads evenly over your hands

and dries very quickly

- Rosin. Rosin is generally available from Theatrical Suppliers (who usually

offer best value on Rosin). When you can find it in theatrical supply shops,

it usually comes in big chunks in big bags. Dance supply shops will also

generally carry it, however it is usually more expensive than it would be at

a theatrical supply house. Last but not least you can often find it in Music

Shops, as string players use it. (hint: You'll want double-bass size)

- Spray Rosin. Spray Rosin is a liquid mixture of rosin and alcohol.

Spray Rosin is more commonly used with aerial fabrics (aka silks, tissue)

- Liquid Rosin

mixture

- Hair Spray is an old-timers trick for better grip

- Anti-Slip Spray. Cramer's "Tuff Skin" and "Firm

Grip" sprays are often recommended. Both of these are available

from various medical supply companies.

5.3 Hand Grips

Q. I would like to have a set of hand grips available for when I have

tares. What kinds of grips are available?

A. A number of people make personalized grips just for the trapeze, while

other use various gymnastics (see the section on Equipment Vendors), and still

other use improvised grips.

Q. What are the differences between the different personalized grips?

A. Each grip has its own advantages and disadvantages. What is right

for you will come down to personal preference. The best advice is to talk

to the vendors of these grips and see what best meets your needs.

Q. What are the differences between the different gymnastics grips?

A. While gymnastics grips generally come in two designs - with the dowel,

and without - this also mostly comes down to personal preference. The

dowel gives your hand more protection, but less feel.

Q. What are improvised grips, and how do I make them?

A. The most common improvised grips are grips made out of athletic tape.

To make a hand grip out of athletic tape, start by taking two lengths of tape

approximately 2-3 inches longer than the length from your wrist to base of your

middle finger. 2-ply it over on itself, then cut a slit about a half inch

from one end to fit over one of the middle fingers while anchoring the other end

against your wrist with a second piece of tape.

The advantages of this kind of grip are that (1) its a good way to feel the

bar (2) its personalized to cover only the parts of the hand that need it and

(3) its inexpensive.

The disadvantages of this kind of grip are (1) if the tape is too tight, it

breaks (2) if it's too long, it won't adequately protect the palm and (3) you

have to make it each flying session.

5.3 Proper Grips

Q. I have heard of something called a "power grip" on rope apparatus

- what is it?

A. A power grip is a method of using your wrist to get better friction on a

rope based apparatus. When most people hold a fabric, the allow their

wrists bend, and we rely entirely on the strength of our fingers to apply

pressure to the fabric to hold us up. The "power grip" is when

we straighten out the wrist so that the fabric bends into a bit z in your

hand. This gives you a lot more friction in your grip - as much as 3x more

friction.

6. Selecting Aerial Apparatus

Choosing the right equipment for you and your needs / situation can be a

tough thing. The following notes should be of some assistance to those that are

in the market for aerial apparatus.

6.1 Selecting an Aerial Hoop

Q. How do I size my aerial hoop?

A. Properly sizing an aerial hoop or Lyra can be a difficult thing to do. So

much of it comes down to individual flexibility, personal preference, and what

you are comfortable with. The following is a very general guide. We highly

recommend speaking with your vendor about what size Lyra you need.

- 34" Lyra is generally best for a performer under 5'6"

- 35" Lyra is generally best for a performer under 5'8"

- 36" Lyra is generally best for a performer under 6'

A second method of selecting an aerial hoop is to sit in a chair, measure

from the seat of the chair to the top of the head, and add an inch.

Q. One Tab or Two?

A. Depends on how you are going to use it, what effect you are after and

what you are comfortable with. The following is list of just a few things you

might want to take into account when choosing your aerial hoop:

- If you do not want your aerial hoop to spin, you want a double tab.

- If you want a trapeze like swing, you want a double tab

- If you want spin, you can use either a single or a double tab (see rigging

section)

- If you want to use your aerial hoop like a dance trapeze, you want a

single tab

- If you want to swing along more than one axis, you want a single tab

Q. Solid, or hollow hoop?

A. This depends on how you are going to use it, specifically the amount any

type of spin you want. A solid hoop has more mass to it, making it harder

to get it spinning than a hollow hoop. Once it gets spinning, a solid hoop

will keep spinning much longer than a hollow hoop will.

In addition to the spin being different, the difference in weight will also

change many of the artistic lines for positions on the hoop. Last but

not least, think about storage, transportation and setup, and how the weight of

the hoop will effect each of these.

Q. Do I want a crossbar on my aerial hoop?

A. Again, the answer to this depends on how you are going to use it, what

effect you are after and what you are comfortable with. If you do not make use

of the bar, or if the bar gets in your way, then you don't want one. If you use

the bar, or if it is part of the effect your after, then you obviously do want

your aerial hoop to have a crossbar.

Q. Should I have hand/foot loops on my aerial hoop?

A. Again, the answer to this depends on how you are going to use it, what

effect you are after and what you are comfortable with. If you use the hand/foot

loop, or if it is part of the effect your after, then you obviously do want your

aerial hoop to have the loop.

In the case of a hand/foot loop, when in doubt it is a good idea to get the

loop. They are inexpensive enough that even if you never use it, its not a big

loss. On the flip side, it can be torture if you have to wait several weeks for

one to come in so that you can do that skill that requires it, or that you don't

yet have the hand strength to do without it.

Q. I want to know more about how an aerial hoop is built, what can you

tell me?

A. In recent months, two excellent articles have been written documenting

how each author built their own aerial hoops.

6.2 Selecting a Trapeze Bar

Q. What kind of trapeze bar do I need?

A. Choosing the Proper trapeze bar can be a difficult thing to do. So much

of it comes down to personal preference, what you are comfortable with, and what

you are doing. We highly recommend speaking with your vendor about what trapeze

bar is right for you.

Some points to think about:

- Padded or unpadded?

- Will you be doing rope work above the bar?

- If so, think about the kind of rope you want to work with.

- Single or multiple?

- How long of a bar should I get?

- Do you want the bar to extend past the ropes, or not?

- How long of a bar do you need to be able to sit comfortably on the bar

with your fists gripping the bar on each side of your hips?

- How thick of a bar do I want?

- Most circus trapeze bars have an outer diameter of �" or

1", while dance trapeze bars are also sometimes found with outer

diameters of 1�" and 1�". You should try

different sized bars and select a bar with the diameter you are most

comfortable with.

6.2.1. Wooden Trapeze Bars

Q. What is the history of wooden trapeze bars?

A. While we have not been able to find the exact origin of wooden trapeze

bars, we do know that they were a popular gym apparatus from the mid-late 1800's

up through the 1930's. Wooden trapeze bars were commonly found in school

and church gyms during that time period. During the period from 1910 to 1930,

trapezes were generally removed from schools, with safety the most often reason

sited for the removal.

Q. Are wooden trapeze bars still used?

A. Surprisingly enough, yes. Many in the aerial dance community swear

by them.

Q. What are the arguments for using wooden trapeze bars?

A. There are several reasons commonly given for using trapeze bars,

including:

- The feel of the wood bars. Many aerial dance performers like the

feel of the wooden bars

- Wood bars can be used un-taped

- Wooden bars are lighter than metal bars

- When they are not on them, wooden bars can be moved around stage by a

performer in such a way they seem to float

- Wooden bars do not have to be taped, this allows the performers to slither

on the bars

- Wooden trapeze bar can give the performer an extra spring from the bar

verses a metal trapeze bar

Q. What are the arguments against using wooden trapeze bars?

A. The following are reasons commonly given for not using wooden trapeze

bars:

- Low safety factor. Wooden bars can have as low as a 2.5:1 normal

safety ratio (see section 8.1 for questions on a normal safety ratio).

- Difficulty in determining the strength of a particular piece of wood.

We are unable to accurately determine the breaking strength of a given

wooden bar due to the imperfections in the wood. This is compounded by

the fact that imperfections may not to noticeable to the naked eye.

Q. Does Simply Circus use or allow the use of dimensional wood trapeze

bars?

A. No, they do not meet our minimum safety factor for use with students.

We may allow the use of metal core and/or laminate wood bars that meet our

minimum safety factor.

Q. Do wooden trapeze bars break in the middle of the bar, or at the ends

where the rope attaches?

A. Most of the breaks that we are aware of happened in the middle of the

bar, however breaks are also known to happen where the bar is attached to the

rope.

Q. Couldn't you use a metal core to get the feel of a wooden bar, and the

strength of a metal bar?

A. That depends on who you ask. Many aerial dancers dislike the

additional weight of a steel or aluminum metal cores, and so will not use them.

In theory, a titanium core in a wooden bar should give a flyer the best of both,

including the low weight of an all wood bar and the strength of a steel bar.

At the time of this writing (11/2006) Simply Circus is unaware of anyone

manufacturing such a bar.

Q. Couldn't you use a laminated wood trapeze bar to get an acceptable

strength, while retaining the weight, feel and other effects of natural wood?

A. In theory, yes, it should be possible to do with a 1-1/4" bar made

from 13 or more laminated layers of hardwood. Laminated layers of wood are

typically a lot stronger than equally sized dimensional wood. The use of

alternating layers will also generally make up for any imperfections found in

any single piece of wood, and allows for much greater predictability of strength

from one piece to the next. These factors would seem to indicate that, at

least in theory, it should be possible to build a laminated wood trapeze bar

with a normal safety factor high enough for student use, yet retaining all of

the benefits of natural wood bars. At the time of this writing (11/2006)

Simply Circus is unaware of anyone manufacturing such a bar, though it should be

within the skill range of most finish carpenters and cabinet makers.

(Note: If anyone does choose to build and load test a batch of laminate

trapeze bars, please share your load

testing data with us)

Q. You said that wooden trapeze bars were used in the 1800's. I

would like to compare construction of those to modern metal bars. Where

can I get information on how those were made?

A. See this

link for information on how people built wooden trapeze bars in the 1860's,

including details on how they strengthened the connectors between the bar and

the ropes.

6.3 Selecting Aerial Silks

Q. What do I need to know about choosing aerial silks / fabrics?

A. When buying aerial fabrics from a vendor that specializes in selling

fabric to aerialists, you want to think about the stretch, width and length of

the fabric you need. (You can also Click Here to Order Aerial Fabrics from Simply Circus)

Low stretch fabrics are easier to climb than medium stretch fabrics, but they

are not as soft for big drops. Medium stretch fabrics are nice for drops, but

are a little harder for beginners to climb. High stretch fabrics are even nicer

for drops, but virtually impossible for beginners to climb.

Aerial Fabrics come in a variety of widths. A 60" width is generally

recommended for children, where as a larger width (75", 90" or

108" widths) are generally recommended for teens and adults. At widths of

75" and above, the choice mostly comes down to a personal or artistic

preference.

Aerial fabrics are generally cut to length depending on the height you are

mounting it to. For beginners, you want the fabric to come down past the ground.

For intermediate users and above, you want the fabrics to come down to the

ground.

Q. I am going down to the local fabric store to buy fabrics for my aerial

act. What do I need to know to do this safely?

A. We advise you in the strongest possible terms to go through a reputable

aerial fabric vendor (many are listed in the Equipment section of this FAQ, or you can (Click Here to Order Aerial Fabrics from Simply Circus)).

If you insist on proceeding, you have a lot of research to conduct, and a lot of

factors to take into account. As most of the aerial fabrics in use are polyester

based, the following selection criteria is based on the use of polyester (Note:

The same general steps should be used for other types of fabrics as well).

Polyester is a man-made fiber. Modern methods of poly processing yield threads

and yarns that are extremely consistent and its properties are well known

(tenacity up to 85 cN/tex), however your research may turn up other

alternatives. Choosing the right fabric for your needs can be at least

somewhat complex, though the following should be enough to get you started:

First, you have to choose from the two primary types of polyester, PET (or

polyethylene terephthalate) and PCDT (or poly-1, 4-cyclohexylene-dimethylene

terephthalate). PET is the more common type, as it is stronger than PCDT, though

PCDT is more elastic and resilient than PET is.

Next you need to know the kind of yarn. Is it a filament yarn (a yarn made

from a single monofilament fiber), a spun yarn (yarn made from thousands of

smaller fibers in much the same way cotton yarn is made), or a blend (spun with

nylon, cotton, etc). Filament yarn is more consistent than a spun yarn, however

the overall difference in strength is small enough that it is hard to notice. Be

aware that nylon blends tend to "pill" much more easily than others

do.

Then you have to select a yarn size (denier). The higher the denier, the thicker

the yarn. For spun poly, 35 denier and above seems to be strong enough for use

in aerial fabrics.

The last things we have to select are the weave (well, knit), the width and the

thread count. Modern machine weaving and knitting techniques make it possible to

get fabrics that are very predictable, and that's one of the most important

things we want in an aerial fabric. While Tricot seems to be the most

popular weave for low stretch fabrics, just about any of the warp knits will

give you the strength consistency and more importantly safety that you need. For

reference, Simply Circus uses a 105 inch wide, 40-denier, tricot weave, 100%

polyester (sorry, I don't have thread count handy). The manufacturer of my

fabrics uses spun PET yarn rated at between 75 and 80 cN/tex.

Q. Has any testing been done on the strength of aerial fabrics?

A. Yes, there has been some testing done, and more is in the works.

- Galvan Wild has conducted extensive material tests. The Circus OZ

testing is not currently available online, however the most recent testing

he has done ("Rip and Tear, Phase 1") is available here

(raw data from those tests is here).

Galvan has more testing planned and under way, we will add links to those

test results as they become available.

- Cypher Zero and FireFly Dance has performed some fairly extensive material

tests, including metered shock loads and pulls, on several kinds of commonly

used fabrics. This data is not online, however Cypher has been

known to share if you ask nicely.

- Cathy Gauch of Aircat Aerial Arts tested the breaking strength of the 100%

polyester knit fabric they use (what others often refer to a super

stretchy). When Cathy Gauch tested the fabric for breaking strength, she

tied it in a slip knot, that was put on to a shackle. It was stretched to

it's max, about 1 - 1.1 tons, twice. On the third time, it started to rip

just below the knot at 1.1 tons (A ton is 2000 pounds, 1.1 tons is

2200 pounds)

- Serenity Smith Forchion of Nimble Arts had pull testing done on 4 fabrics

in June of 2007. Two of the fabrics were low stretch (also called no

stretch) and two were medium stretch.

- The first fabric was a new 114" wide, low stretch tricot fabric,

which broke at 2025 lbs.

- The second fabric was a used (4 years old) 96" wide low stretch

tricot fabric, which broke at 1795 lbs

- The third fabric was a new 60" wide medium stretch interlock

fabric, which broke at 850 lbs. It should be noted that this

sample was not the normal medium stretch interlock fabric they sell.

- The forth fabric was a used 60" wide medium stretch

interlock fabric, which broke at 1310 lbs.

- Aerial Fabrics pull testing done in May

2007 by Phil Servita. Currently, this is the most well-documented

test of aerial fabric publicly available.

Q. In the strength testing that has been done on aerial fabrics, have the

failures been catastrophic?

A. As far as we are aware, none of the strength testing that has been done

has resulted in a single catastrophic failure of the fabric. All of

the testing that we are aware of resulted in significant tearing well before the

fabrics broke.

Q. What are 'fire proof' aerial silks?

A. As of this writing (1/2007), there are no fabrics on the market that are

certified as fire proof, nor are there any products on the market that can make

a fabric fire proof. If a fire gets hot enough all fabrics will burn or

melt (including synthetics). The best you can do in terms of making

your aerial silks safer in a fire is to make them flame retardant.

Q. What do I need to know about fire retardants?

A. Fire retardants are chemicals that make it harder for a fire to burn.

Most synthetic materials have fire retardants mixed in during manufacturing,

while other materials will need to have them added later. These retardants

give you more time to get out of danger before the materials its applied to goes

up in flame. As an aerial performer, you will, from time to time, run into

situations where you need use and prove that that you are using aerial silks

that have been treated with a fire retardant.

Q. OK, I need to prove my silks are fire retardant. How can I do

this?

A. Some jurisdictions (such as NY and CA) require you to obtain official

certificates from either the manufacturer of the fabric, or from a certified

fire retardant treatment company. Most jurisdictions will accept end-user

treatment records. If you foresee this as being an issue, the easiest

thing to do is to ask your aerial silks vender for a certificate of flame

retardancy when you purchase new silks. Be aware that most silks vendors

are distributors, and will likely need to obtain these from the manufacturer

before they can give them to you.

Q. Are the silks I bought already flame retardant?

A. Since most aerial silks in common use today are made from synthetics,

they very well could be. You should ask your vendor about this.

Q. My silks are not currently fire retardant or I can't prove that they

are. What can I do?

A. Your only options are to (1) buy new silks with the fire retardant

certificate, or (2) treat the silks with a chemical retardant. Depending

on where in the world you are, you may be able to treat it yourself, or you may

need to hire a company to treat it for you.

Q. What do I need to know about treating these myself?

A. Because of how silks are used, you need to use a fire retardant chemical

that can be in constant direct contact with the skin. In general you

should look for a class 1 flame retardant spray that specifically lists

'Bedding' or 'Clothing' as an approved area of application (note: some chemicals

list 'mattresses,' this is not the same as 'bedding.')

If you treat the fabrics yourself, the following tips should be helpful:

- MAKE SURE YOU READ AND UNDERSTAND THE LABEL BEFORE APPLYING IT TO

ANYTHING!

- Make sure you apply these chemicals in a well-ventilated area

- Use proper protection when applying these chemicals (chemical gloves,

water proof boots, chemical mask, eye protection, long sleeve clothing,

etc.)

- Do the math. The label will tell you how to calculate the amount of

product needed for the size of your fabric. Make sure to do the math,

and use the amount of product the label says to use.

- LET THE FABRIC AIR DRY COMPLETELY AFTER TREATING THEM

- All fire retardant products will make the fabric a bit stiff, kind of like

if you had added starch when you washed them. The best way we have found to

counter this is to place the fabrics in a dryer on tumble only (no heat), or

on the lowest heat setting the dryer has, and allowing the fabrics to tumble

until it is soft again. This should not have any effect on the fire

retardant. MAKE SURE THE FABRICS ARE COMPLETELY DRY BEFORE DOING THIS!

- Make sure you document what you used, when you used it, how much chemical

you used, how you applied the chemicals to the fabrics, and when you expect

to have to reapply treatment (usually once every 2 years).

- Some of these products also include a list of things to watch for with

treated fabrics. These watch list items should be added to your

regular inspections of the fabrics.

Q. What do I need to know about having a company treat these for me?

A. Because of how silks are used, you need to make sure they use a fire

retardant chemical that can be in constant direct contact with the skin.

The chemical they use should be a class 1 flame retardant that specifically

lists 'Bedding' or 'Clothing' as an approved area of application.

If you have a company treat the fabrics for you, the following tips should be

helpful:

- Make sure you get all of your paper work. This includes a

certificate of treatment, a service slip or receipt with the chemicals used,

and copies of both the MSDS sheet and specimen label for the chemical they

used. You should keep all of these for your records.

- Make sure the service slip or receipt they give you lists the chemical

they used, and the amount of the chemical they used.

- Check there math. The label will tell you how to calculate the

amount of product needed for the size of your fabric. Do the math

yourself, and check that against the amount of product they actually used.

- All fire retardant products will make the fabric a bit stiff, kind of like

if you had added starch when you washed them. If the treatment company does

not tumble the fabric for you, you should tumble it yourself (see the

section on treating the fabrics yourself)

- Some of these products also include a list of things to watch for with

treated fabrics. These watch list items should be added to your

regular inspections of the fabrics.

Q. Do these chemicals affect the strength of the fabrics?

A. Yes, they do. Many of the fire retardant treatments that are in common

use today work because the chemicals that are applied react with the cellulose

of the material they are applied to. It is virtually impossible to have a

chemical reaction of this type without the cellulose being weakened in the

process.

While its extremely difficult to calculate the exact strength reductions

(this will depend on details of the fabric, the chemicals used, the application

and other factors), as a general rule of thumb you can assume that treated

fabrics are about 10% weaker than non treated fabrics.

6.4 Selecting a Web

Q. What are webs?

A. A web is the ropelike apparatus used in various aerial acts, including

Spanish Web, Corde Lisse and Cloud Swings. All

webs have an eye spliced into either one or both ends of the web for rigging

purposes. Some webs have steel cable cores, while most do not.

Q. Where did webs come from?

A. Webs evolved from the rigging ropes used by the early Spanish Web players

(it began as a climbing game played by Spanish sailors as early as the 1300's),

to the modern webs we use today.

Q. What kind of webs are available today?

A. In general, their are two basic kinds of webs to choose from - Braided

Webs (left) and Tubular Webs (right).

Q. How are braided webs constructed?

A. Braided webs are made out of thick (usually 30mm-35mm diameter), strong

(usually rated with a BS n the 7,000# plus range) but soft 8-strand braded rope

with an eye splice done in one or both ends of the web. Because these

ropes are commercially available and the splicing is not too difficult, these

webs are made by many independent riggers, and are also sold by various circus

equipment venders.

Q. How are tubular webs constructed?

A. Tubular Webs were originally made by pulling large numbers of cotton

yarns (the kind ropes are made of) through old textile fire hoses.

Modern webs are still made in much the same way, with rope fibers being

pulled through a textile sheath, however modern webs are made with much better

materials than the early webs were made with (modern cotton webs have a BS in

5,000# range, and synthetic webs can have BS ratings well over 10,000#).

Commercially available tubular webs can be purchased from a number of sources,

though almost all are actually manufactured by the same company. Tubular

webs can also be custom made by some independent riggers. While cotton is still

the most popular material for making tubular webs (almost all commercially

manufactured webs are made of a cotton sheath and a 50/50 cotton poly blend

internal rope), it is becoming more common to find tubular webs made of nylon

and other synthetic materials.

Q. Which kind of web is right for me?

A. That mostly comes down to personal choice. Some people like the feel of

braided webs, while others like the feel of tubular webs.

Q. What's the deal with webs and steel cable cores?

A. The need for steel cable cores in webs is a debate that rages on and off

again in various rigging circles. Early tubular webs were made with less than

deal materials, and needed steel cable cores for basic safety. Modern webs are

constructed with much higher quality materials, and usually don't need cable

cores for general use. At the end of the day, the bottom line is that some

applications require a cable core, but most don't.

Q. What are some examples of situations were I might need a cable core in

my web?

A. In some situations, webs can be exposed to high shock-load forces where

you might want a cable core to take that load. Sometimes you will rig a

web to support another apparatus. For example, you might want to have two webs

supporting a double trapeze. In such a case, you may want the cable core

to help make sure the trapeze bar is always level.

Q. Why wouldn't I want a cable core in my web?

A. Webs with cable cores are harder to wrap around the body, they are harder

to get hold of, they are much more expensive, and they are much harder on the

body of the performer.

7. Inspecting and Maintaining Aerial Apparatus

What follows are very general guidelines for inspecting and maintaining

various pieces of aerial apparatus. These guidelines are NOT a replacement for

the specific maintenance and care instructions that came with your equipment.

7.1 Metal Apparatus (Lyra, Trapeze Bars, etc)

Most metal apparatus, including Lyras and Trapeze Bars, are solid pieces of

equipment that should last a very long time if properly maintained. While the

exact inspection schedule will depend on factors such as the amount of use a

particular apparatus gets and the manufacturers instructions, as a general rule

of thumb a cursory inspections should be made every time the apparatus is put

up, or for fixed installations on about a weekly basis and a full inspection

done on at least a yearly basis.

7.1.1 Cursory inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Check the body of the apparatus for any signs of rust according to the

manufactures instructions.

- If you find rust on the body of the apparatus, you should rub the area

with steel wool to remove the rust.

- If you find rust over a large portion of the unit, or going into an

area covered by padding/fabric, perform a full inspection on the unit.

- Check the welds according to the manufactures instructions.

- Look for any surface flaws of imperfections in the weld.

- Using hand pressure, try and pull and twist the weld.

- If the welded joint fails this inspection, immediately take the unit

out of service and consult the manufacturer.

- Inspect any attached ropes or cables according to the manufactures

instructions.

- If the ropes or cables show any imperfections or signs of excess wear,

perform a full inspection on the unit

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

7.1.2 Full Inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Disassemble the unit according to the manufactures instructions

- Remove any grip aids (tape, etc) from the unit

- Remove any fabric coverings and padding from the unit per

manufacturers instructions

- Remove and rigging components (shackles, etc) and ropes / wires from

the unit

- Clean the unit according to the manufactures instructions

- Most metal items can be cleaned using rubbing alcohol and rags

- Make sure to get all grip aid residue off

- Check the body of the apparatus for any signs of rust according to the

manufactures instructions

- If you find rust on the apparatus, you should rub the area with steel

wool to remove the rust

- Check the welds according to the manufactures instructions

- Look for any surface flaws of imperfections in the weld

- Using hand pressure, try and pull and twist the weld.

- If the welded joint fails this inspection, immediately take the unit

out of service and consult the manufacturer

- Inspect any attached ropes or cables according to the manufactures

instructions.

- If the ropes or cables show any imperfections or signs of excess wear,

replace the ropes or cables

- Inspect any rigging components according to the manufactures instructions.

- If the rigging components show any imperfections or signs of excess

wear, replace the components

- Inspect the padding and fabric covers according to the manufactures

instructions.

- If the padding or fabric show any signs of excess wear, replace the

padding and/or fabric

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

- Reassemble the unit according to the manufactures instructions.

- This is generally done in the reverse order of how you disassembled it

- Re-tape the unit

7.2 Rope based Apparatus (Spanish Web, Corde Lisse, Cloud Swing)

Most Rope based apparatus, including Spanish Web, Corde Lisse and Cloud

Swings, are durable, long lasting pieces of equipment when properly cared for

and maintained. Webs do need to be replaced as they get worn over time. In

general, and unless otherwise specified by the manufacturer, a cursory

inspections should be made every time the apparatus is put up, or for fixed

installations on about a weekly basis. A full inspection should be done on

at least a yearly basis, and a pull test done once every 1-5 years.

7.2.1 Cursory inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Disassemble all rigging

- Check the body of the web according to the manufactures instructions.

Check

the outside of the web for tears, cuts and other signs of excess wear on

the web. Hold the web with your hands 6 to 8 inches apart and bend the

web in an inverted "U" as shown. This bending will make it

easier to see any damaged fibers or cuts that may be present.

Inspect entire exterior of the web. Check

the outside of the web for tears, cuts and other signs of excess wear on

the web. Hold the web with your hands 6 to 8 inches apart and bend the

web in an inverted "U" as shown. This bending will make it

easier to see any damaged fibers or cuts that may be present.

Inspect entire exterior of the web.- If the web has any minor tears or cuts in it, or otherwise shows

other signs of excess wear, document the damaged area and increase the

inspection frequency. If the minor damaged area increases in size or you

find major damage replace the web.

- Smell the web

- If the web smells mildly, apply Febreze or another spray on

fabric odor control product to the material to control the smell

- If the odor can not be adequately controlled with a spray on fabric

odor control product, perform a full inspection

- If you smell mold, mildew, or dry rot replace the web

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

7.2.2 Full inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Disassemble all rigging

- Check the body of the web according to the manufactures instructions

just as you would do in your cursory inspection.

- Wash the rope according to the manufactures instructions.

- Gently hand wash the straps use as little moisture as possible in the

cleaning process. This moisture will potentially damage the web if not

completely dry.

- Use a mild detergent only (do not use softeners, bleach, etc)

- Allow the web to hang dry - DO NOT use a dryer, and DO NOT hang in

direct sunlight

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

- When completely dry recheck the body of the web according to the

manufactures instructions as was done in step 3 and 4 of the cursory

inspection

7.2.3 Pull inspection

Pull tests are tests that are generally conducted by the manufacturer every

few years. The manufacturers generally inspect these units by pulling it

with 1000 pounds for 30 minutes, and performing a more in-depth version of the

full inspection listed above. In general, you should be sending the the swivels

and other rigging components as well so they can be disassembled,

inspected, and (if needed) lubricated.

7.3 Aerial Fabrics

Aerial Fabric needs to be replaced as they get worn over time. In general,

and unless otherwise specified by the manufacturer, a cursory inspections should

be made every time the apparatus is put up, or for fixed installations on about

a weekly basis and a full inspection done on at least a yearly basis. Remember

that using a slip-knot, or using the fabric as a sling is harder on the

material, and you should adjust your inspection schedule accordingly.

7.3.1 Cursory inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Remove the fabric from the Fabric from the Fabric Hanger or Rescue-8

- Check the body of the fabric according to the manufactures instructions.

- Check for tears in the fabric or signs of excess wear

- If the fabric has tears in it, or shows other signs of excess wear,

replace the aerial fabric

- Smell the fabric

- If the fabric smells mildly, apply Febreze or another spray on fabric

odor control product to the material to control the smell

- If the odor can not be adequately controlled with a spray on fabric

odor control product, perform a full inspection

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

7.3.2 Full inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Remove the fabric from the Fabric from the Fabric Hanger or Rescue-8

- Check the body of the fabric according to the manufactures instructions.

- Check for tears in the fabric or signs of excess wear

- If the fabric has tears in it, or shows other signs of excess wear,

replace the aerial fabric

- Wash the fabric according to the manufactures instructions.

- Use a front-loading machine if possible

- Use detergent only (do not use softeners, bleach, etc)

- Allow the material to hang dry - DO NOT use a dryer

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

- Recheck the body of the fabric according to the manufactures instructions.

- Check for tears in the fabric or signs of excess wear

- If the fabric has tears in it, or shows other signs of excess wear,

replace the aerial fabric

7.4 Straps

Straps need to be replaced as they get worn over time. In general, and unless

otherwise specified by the manufacturer, a cursory inspections should be made

every time the apparatus is put up, or for fixed installations on about a weekly

basis and a full inspection done on at least a yearly basis.

7.4.1 Cursory inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Disassemble all rigging

- Check the body of the strap according to the manufactures instructions.

Check

both sides of each strap for tears, cuts and other signs of excess wear

in the strap. Hold the webbing with your hands 6 to 8 inches apart and

bend the webbing in an inverted "U" as shown. This bending

will make it easier to see any damaged fibers or cuts that may be

present. Inspect one side, then turn the strap over and inspect

the other side. Repeat with the second strap. Check

both sides of each strap for tears, cuts and other signs of excess wear

in the strap. Hold the webbing with your hands 6 to 8 inches apart and

bend the webbing in an inverted "U" as shown. This bending

will make it easier to see any damaged fibers or cuts that may be

present. Inspect one side, then turn the strap over and inspect

the other side. Repeat with the second strap.- If the straps have any tears or cuts in it, or otherwise shows other

signs of excess wear, replace the straps.

- Smell the straps

- If the straps smell mildly, apply Febreze or another spray on fabric

odor control product to the material to control the smell

- If the odor can not be adequately controlled with a spray on fabric

odor control product, perform a full inspection

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

7.4.2 Full inspection

- Remove the apparatus from the rigging

- Disassemble all rigging

- Check the body of the strap according to the manufactures instructions

just as you would do in your cursory inspection.

- Wash the straps according to the manufactures instructions.

- Gently hand wash the straps

- Use a mild detergent only (do not use softeners, bleach, etc)

- Allow the straps to hang dry - DO NOT use a dryer, and DO NOT hand in

direct sunlight

- Check the rigging components for signs of excess wear

- If any rigging component shows signs of excess wear, replace the

component

- Recheck the body of the straps according to the manufactures instructions

as was done in step 3.

8. Rigging

8.1 General Rigging Questions and Theory

Q. Will reading FAQ make me a qualified rigger?

A. No!! If you even think it will, stop reading this FAQ now before you kill

someone!

Q. What process does a rigger use to figure out how to rig something?

A. How an individual rigger does this varies from rigger to rigger, however

most professional riggers use a process known as "Weak

Link Analysis" (WLA for short) whenever they design, build or rig any

sort of aerial rigging. WLA is the process of systematically examining each and

every component of a rigging setup to find the weakest link. Once identified,

the rigging is designed and built with that weakest link in mind, and with the

desired safety factor.

While this sounds like a simple process, it is not. Many factors can make

rigging even simple effects a very complex task. Riggers will often have to

combine components that are designed, measured and tested in the SI system

(metric system), with components that are designed, measured and tested in

English units. Some components will have a working load limit and an ultimate

load limit. Some will only include a working load limit, and other only a mean

breaking strength (MBS). Then you might have to get into the reductions required

by manufacturer specifications for angular loading, additive loads, bending

around sheaves, as well as termination efficiency. All of this adds up to a very

complicated process.

Q. What is a "Shock Load"?

A. A shock load is defined as the sudden and rapid application of force

placed on the rigging. In aerial arts, shock loads are fairly common, and can be

caused by performing skills such as drops.

The formula for computing the minimum shock load is: Shock Load = [(W x Df) /

Ds] + W, where Df is the freefall distance, Ds is the stopping distance, and W

is the weight of the falling object.

For example, lets say we have a a 220 pound (~0.98kN) silks artist that does

a 9 foot free fall and then suddenly stops over a 3 foot distance. Applying our

formula, we get:

| Shock Load=[(W x Df)/Ds]+W |

| 880lbs=[(220lbs x 9 feet)/3 feet]+220lbs |

As you can see, this gives us a minimum shock load of 880 (~3.91kN) of force

on the rigging (at about 4g's)

Q. I have been told that I should have at least a 10:1 safety ratio. What

does that mean?

A. There are two very different answers to this question. A safety ratio can

be calculated using either the equipments normal load (more common), or its

potential shock load (less common). When using a normal load, the safety ratio

is the ratio between the normal expected load of the equipment, and the breaking

point of the weakest point of the rigging. When using the shock load, the safety

ratio is the ratio between the largest expected shock load a rig is expected to

take, and the breaking point of the weakest point of the rigging. To put this in

perspective, we will take a brief look at rigging aerial silks.

As discussed in the last question on shock load, in theory, a 220 pound

person (~0.98kN) could put 880 pounds (~3.91kN) of force on the rigging. Various

load testing has shown aerial fabric to have a breaking load of about 1.1 tons

(2,200 pounds or 9.78kN). Our rescue-8 has a MBS rating of 10,000 pounds

(44.48kN). Our carabineers are MBS rated at 72kN (~16,000 pounds) , and our

swivel MBS rated at 36kN (~8,000 pounds). We will assume an aerial mount point

with a MBS rating of 2 tons (4,000 pounds)

| Component |

kN |

Pounds |

Safety ratio

(normal) |

Safety Ratio

(shock load) |

| Mount point |

17.79kN |

4,000lbs |

18:1 |

4.5:1 |

| Carabineers |

72.00kN |

16,000lbs |

72:1 |

18:1 |

| Swivel |

36.00kN |

8,000lbs |

36:1 |

9:1 |

| Carabineers |

72.00kN |

16,000lbs |

72:1 |

18:1 |

| Rescue 8 |

44.48kN |

10,000lbs |

45:1 |

11.3:1 |

| Fabrics |

9.78kN |

2,200lbs |

10:1 |

2.5:1 |

As you can see from the chart above, the weakest link here is the fabric

itself, with only a 10:1 safety ratio, followed by the mount point with an 18:1

ratio. This means that the normal safety ratio for our aerial silks is 10:1,

with a weight limit of 220 pounds. Our shock load safety ratio for our silks is

2.5:1, with a weight limit of 220 pounds.

- "For a 220 (~0.98kN) pound aerialist to do something on a silks

setup that would cause them to produce 2,200lbs (9.78kN) of force on the

fabrics, that performer would experience the equivalent of 10g's of force -

more than enough to cause blackout and possibly internal injuries before the

equipment would give away." -Chris Clark

- "For a 140 pound (~0.62kN) person to produce the same 2,200lbs

(9.78kN) of force on the fabrics, that performer would experience the

equivalent of 15.66g's of force - more than a fighter pilot experiences

during an ejection - before reaching the breaking point on the fabric. It

should be noted that the military will only allow pilot's to experience such

eject force twice before grounding them permanently." -Chris Clark

The best advice is to make sure that you know and understand what safety

factor your rigging is designed and built with, and make sure that you

understand what the week points in your rigging are. Whenever in doubt, check

with your own qualified rigger!

Q. What safety ratio should I design my rigging to have?

A. In general, you want at least:

| Who |

For What |

Safety ratio

(normal) |

| General Public |

Systems designed to be used by a member of the public,

including youth circus participants, should be rigged at a 10:1 or

greater safety ratio. |

10:1+ |

| Heavy use |

Heavy use systems can be used with confidence in both the

strength and the longevity of the equipment. Thorough and

regularly scheduled inspections of the equipment are, as always,

essential to safe use.

Systems that take significant shock loads, are not easily expendable,

or are not easily inspected should be designed to at least this range of

safety ratios.

|

5:1 - 10:1 |

| General use by trained Aerialists |

System that are built in this safety range can generally

be used over and over again with reasonable variations in movement as

long as the force put on the system is not significantly increased or

altered from how the rig is designed to operate.

Equipment in this range require frequent, regularly scheduled

inspections with immediate replacement of parts that are suspected of

excess wear.

|

3:1 - 5:1 |

| Static Equipment or Limited supervised use. |

Any system created or built with a safety factor in the

2:1 - 3:1 range should only be used for static equipment, or done for a

very specific function. Any rigging done in this range must not be

used in any way for which it is not specifically intended.

Any time such a rig is used to support a performer the rig must be

under constant observation by someone who understands the forces, nature

and tolerances of the system.

|

2:1 - 3:1 |

| Highly trained professionals |

Effects rigged in this range leave almost no margin for

error, and should only be rigged by experienced professional riggers,

and flown by highly trained personnel.

As a general rule, any time you have an effect rigged within this

safety range, it should be viewed as a one time only stunts or effect,

requiring a complete inspection of all components before and after each

use.

When you have a system with this low of a safety factor, the people

using this system (including others put at risk by this system) MUST be

both willing and able to assume responsibility for the very significant

risk they are taking, including the dangers of potential failure.

|

1:1 - 2:1 |

Q. Should I use the rated strength or the breaking strength when assessing

my rigging?

A. You should always use the breaking strength. In the world of circus

rigging, we often use parts that are designed for other industries. In the

worlds of sailing, theatre rigging and construction rigging (among others),

manufacturers will often give a load rating and not a breaking strength.

In circus rigging, you should convert all rating to a mean breaking strength if

possible.

Q. Why do manufacturers give a safe working load, and not a breaking

strength?

A. Depending on the industry the equipment is coming from, they can do this

for one of many reasons, but most often it is to comply with OSHA

code. Other reasons include sales reasons (such as giving a little in the

safety margin in order to round up the rated load), or competitive reasons (not

wanting a competitor to know exactly how strong a component is)

Q. What does OSHA say about safety factors?

A. OHSA code was, and is, written for equipment that is built for general

use by any person. Unfortunately this means that OSHA does not have standards

that are directly applicable to circus rigging (or theater rigging).

However, throughout most of the various OSHA rigging standards (material

handling standards, Hoisting and rigging standards and Maritime standards), a

5:1 safety ratio is recommended for non human loads and a 10:1 safety ratio for

human loads. These ratios do make for a good starting point for circus

rigging, however you do need to look at your forces to determine what your

safety factor should be..

8.2 More on Weights and Measures

One of the difficulties with rigging circus apparatus is that we end up using

rigging components from many different industries, almost none actually designed